I’ve been working on this over the last month. It’s still unfinished, but I wanted to share an excerpt. These memories exist just below the surface, so close that I can touch them.

1985–1988/Color/Voice/Imagination/Chest Filling With Air/Throat Chakra/Forgetting/Seen, Never Heard/Separation/Loss/Displacement/Projection/Mother Wound/Whitney Filled It/MTV/Memories/Orange Bronco/Rearview Mirror/A Silencing/Sunday Morning Church Service/Remembering/Recognition/Knowing/Separation/Laughter/Shame/Joy/Smiling/

My mother sings. At varying times throughout her adult years, professionally. Beautifully. At weddings and other events. She even recorded an album. The first time I heard her sing, I remember thinking it was impossible such power could come out of such a tiny woman. Suddenly, she was no longer a woman I knew as my mother—instead, she was a force, a mystery, an enchantment. Her voice called me forward from the deep recesses within me I had already learned to withdraw to for safety.

She was in her late 20s. I was six. She was remarried. It was my first summer visiting her after a new custody arrangement had been worked out in court with my father and their divorce had been finalized. We were in a Sunday church service in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia. Ushers were busy passing out fans to help congregants wave away the heat that emanated from bodies dressed in their Sunday best pressed into pews in late June. Service always started with a processional of whichever choir was slated to sing that morning; pastor and church leaders, everyone in the congregation on their feet, hands matching the beats of the drums, throats vibrating with song, feet matching the flairs of the organist, everyone marching in a cadence that left me transfixed when I experienced it for the first time.

My mother directed the young adult choir, but was often called upon to do solos with the adult one, especially if the pastor requested “Order My Steps”. It was the first song I ever heard her sing. It terrified me as much as it mystified me because it awakened emotions in me I couldn’t understand. Her high soprano packed a punch as she sang the lyrics, the height of her notes lifting the congregation to their feet once she started the second verse in her upper register. Her voice swelled above the shouts of the congregation, touching every corner of the building and filling the corners of my eyes with tears.

I do not sing. It’s a running joke in my family that the gift of song skipped over me and was instead given to my siblings. I spent years wishing it hadn’t and that it was a source of joy instead of a wound. Now it’s just something I mine for fun, being that person who randomly bursts into theatrical singing for comedic effect, like Jessica Day (from New Girl) or Titus Andromedon (of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt), effectively making light of what used to feel too heavy to carry. For years, allowing others to hear my voice express itself through song was something I truly struggled to do without deep feelings of embarrassment and shame, which is the exact opposite of what I remember feeling in my earliest singing-related memory.

Years ago, my mother told me that the first time she heard me sing was in 1984 when I was two years old. She said I was standing in front of the television, watching Prince do his slow crawl out of that white bathtub in the video for “When Doves Cry” and singing the song word for word. I was a toddler then, so this is not a memory I have ever been able to locate within myself, but the first singing memory I can actually retrieve includes a song from my other favorite artist during my early childhood: Whitney Houston.

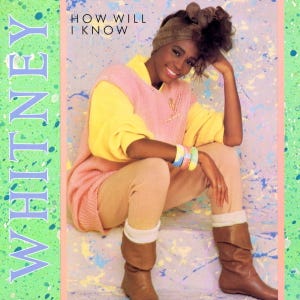

Whitney’s videos from her self-titled album and subsequent follow-up “Whitney” were absolutely mesmerizing to me as a child. Specifically, “How Will I Know” and “Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me)” captured my attention even more than her voice. I was in love with the bright, bold colors and vibrancy dancing across the television screen, her big smile full of white teeth, and the blonde highlights in her hair framing her face. She was radiant. I remember marveling that such a powerful sound could come out of such a tiny woman. The more I think about it, it’s quite possible that 5- or 6-year-old me fell in love with Whitney because she reminded me of my own mother, who I had just been taken from a couple of years prior. Photos of my mother during my toddler years show a young Black woman in her very early twenties with blonde highlights in her feathered or curly hair, exact same body type, and a face similar to Whitney; thin with big teeth and a smile that lit up her entire face. The one photo that always comes to mind when I think of my mother during this time period shows swipes of electric blue eyeshadow across her eyelids. Maybe my fascination and deep love for the Whitney of the mid-to-late 80s was really just a projection of the deep love I had for the mother I was with one day and literally taken from the next without warning. Perhaps Whitney and the visuals of her dancing and singing before my eyes then served as a container for a grief and longing I was unable to express for the mother I was missing—a visual receptacle for my memories of her to stay alive. Maybe it was the way my subconscious channeled the trauma of such displacement and disrupted attachment into something much gentler for me to hold safely in my mind and body without fracturing at my core.

Whatever the case, I loved me some Ms. Houston. So much so that when “Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me)” came on the radio during a drive home in my father’s truck, I forgot myself and sang along, joy fortifying my vocal cords as I sang the lyrics with the same force and sass Ms. Houston does in the video. We lived in Alaska at the time, on Eielson Air Force Base. I don’t recall where we were coming from, but I remember seeing cotton candy pinks, blues, and oranges in the sky when I stared out the window. I was in the backseat of my father’s red-orange bronco. I was sitting in the middle seat so I could see my father’s ink-black eyes clearly every time he looked up. They clouded over with a flash of anger as he broke out into a laugh that lacked any warmth. From the side, I could see the corner of his lips curling upward into a sneer as he told me to shut up. “What makes you think you can sing? You can’t, so don’t even try. Nobody wants to hear you.” I did as I was told. I knew I deserved it and felt shame ooze its way through me like mud. My father didn’t like to be reminded that he had a child, nor did he recognize such spontaneous outbursts as normal child behavior. Not in his presence at least. I’d broken one of his cardinal rules to be barely seen and never heard.

This particular day the consequences weren’t physically violent, but his words climbed deep into my subconscious memory and settled there. They quickly closed my mouth shut and the next time I heard Houston’s “How Will I Know” and wanted to sing the chorus with her. I pressed my eyes tightly shut and pulled what images I could recall from the video from my memory bank, channeling my desire to sing it into envisioning myself dancing with Whitney. His rebuke caught me off guard years later during a performance in a school Christmas play. We were singing one of the last songs when I caught his eye in the audience and remembered. My voice faltered as his words loudly resurfaced in my memory, but my joy over being able to sing wouldn’t allow me to stop. I thought of my mother singing in front of the church and how her voice lifted people out of their seats and water out of my eyes. With every note in each song we performed, I pictured myself as my mother, feeling a sense of pride I didn’t understand, wishing she was there to watch me. I was in 5th grade then. After the play, in the car, all he could talk about was how I reminded him of Sebastian, the crab from The Little Mermaid, as I stood with my classmates and sang my heart out. He laughed about this the entire ride home, poking out his bottom lip as he mimicked my singing face and bellowed “Under The Seeeeaaaaaaa!” in a terrible Jamaican accent. He alternated between making fun of my “big bottom lip” and my singing voice for the next few weeks.

There’s more to say about these memories and this painting’s relationship to them, but I’ve been stuck on what to write next. I’m going to give it a rest for a couple of days and see if that helps me find the words to continue.